This is a how-to for temporarily attaching a strap to a classical guitar. It’s a DIY job and not particularly elegant, but it’s cheap, it doesn’t require much assembly, and I’ve tested it through a number of operatic performances that additionally required people other than myself to handle the guitar on stage. If you need to put a strap on a guitar for an unusual performance, or perhaps if you have back trouble and want to experiment with playing standing up without first committing your guitar to ‘surgery’ to have pegs installed, this is for you.

Some time ago, I had the fabulously good luck to join an opera, namely The Neemrana Music Foundation’s production of Pablo Luna’s zarzuela (Spanish ‘pocket opera’) El niño judío – as a guitarist of course, but as a guitarist in costume, on stage, and singing with the chorus a couple of times! Needless to say, it was a thrilling experience that taught me a lot, introduced me to a number of wonderful and phenomenally inspiring people, and allowed me to address aspects of being a musician that predominantly solo-playing classical guitarists seldom have to – or get to – think about. But much more on that in my next few posts, because as you will know from my title and opening description, this one is about a relatively small – and yet quite essential – logistical aspect of the whole experience.

When I joined the production early in April, I learnt that I would have to play standing up. Not wanting to install pegs on any of my classical guitars, I spent some time looking for alternative solutions. After waiting for suction cups that never arrived in the mail, and talking to a couple of luthiers, here’s what I came up with – it allows you to wear your guitar with a normal guitar strap, you can set it up and remove it yourself, and it will leave no trace on your precious instrument. I should mention at the outset, though – you should only try this with guitars finished in PU, lacquer, or nitrocellulose, as it involves adhesives that would very likely damage a french polish finish.

To do this, you’ll need the guitar you have in mind, of course, and all of this:

…which is to say, the guitar strap you’ll use, some ordinary velcro (2 standard-sized lengths, or about 2′ in total), 3M or similar double sided rubberized tape of the sort you’d find in a car accessories store, Super Glue-style quick drying adhesive (as pictured, in India that would be Fevi kwik), and a bit of plastic sheet.

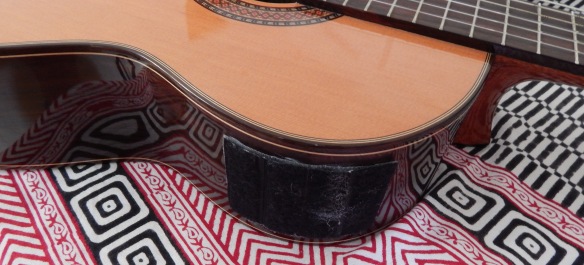

Here’s what you’ll need to do: the double sided tape goes on the guitar, the plastic sheet sticks to it, and you use the quick drying glue to stick the fuzzy side of the velcro to the plastic sheet. (Glue the velcro to the plastic before sticking it to the tape on the guitar, so as to minimize the risk of messing up the guitar finish with the glue) Create two approximately square patches like this, one on the bottom of the guitar (where the two sides meet), and the other on treble the side of the upper bout. You should end up with something like the photo below.

Note that I have stuck these two patches a little below the guitar top, so that they’re not conspicuous on the instrument when you’re playing it. Here’s a closer look at the two patches, for positioning:

Use the same glue to stick the side of the velcro with the hooks in it to the ends of the guitar strap, with the velcro strips going along the length of the strap ends.

While standing, hold the guitar in an ergonomic playing position to figure out how it would rest against you, and make a note of the approximate angle at which the strap would leave the guitar from the two velcro contact points to wrap around you. Stick the strap’s velcro ends on the guitar’s velcro patches at this angle. It should look something like this:

And you’re done! You’re ready to sling it over your shoulder, stand up, and start playing. Here’s a shot of my strapped-up guitar (and me!) doing just that, accompanying soprano Shireen Sinclair on De Espana Vengo.

Before I let you go, it’s important that you note a few details:

- The velcro attachment is easily strong enough to hold up the guitar, but directionality is very important. The velcro’s grip is sound really only when force (gravity, usually) is applied along the direction in which the ends of the strap are attached to the guitar. If the strap is attached so the ends want to twist the velcro attachment sideways or pull up and away from the guitar, the velcro might give way.

- If you’re holding the guitar by the strap, say if it isn’t slung over your shoulder, it’s important for the reasons I mentioned in the previous point to not lift the strap so the guitar is pulling directly away (downwards) from the nearest velcro contact point between guitar and strap. An example of what not to do would be grabbing the strap at one end and lifting it, so the nearest contact point faces upwards, and the weight of the guitar is pulling directly away from the velcro.

- When detaching the strap from the guitar, always lift the velcro strap end from the tip, peeling it off the guitar in the direction of the strap. Also, it’s a good idea to hold down the velcro patch on the guitar while doing this. This will minimize the force applied to the adhesives attaching the velcro to the strap end and the patch to the guitar.