If you read this blog, I’d call it a fair bet that you’re either a guitarist, or someone who digs the music, or both. In either event, if you’ve managed to find my little corner of the matrix, it’s fair to say you’re pretty well plugged in to the internet’s classical guitar scene – I expect in that case that you’re already familiar with Bret Williams’ podcast. In any event, on the off-chance you’re not, and because I’m going to be talking about stuff Bret covered recently in an interview with music management visionary Alvaro Mendizabal, here’s a link to the podcast homepage. I strongly suggest you check it out if you haven’t already.

http://www.bretwilliamsmusic.com/ClassicalGuitarInsider/

In the show, Alvaro and Bret talk a lot about the elephant that sits in the corner of most of our practice rooms – the economics of it all. Or rather, the significant lack of a market that’s large enough to support the size of our sector (that’s us, folks – unsexy a way to put it as it may be, as far as putting food on the table goes, we’re a niche group of producers within a niche sector of the entertainment industry). Alvaro has a lot of interesting ideas (as does Bret, actually) about how the guitar needs to work harder to really join the mainstream classical music tradition, and get out of the eclectic corner it has been painted into inadvertently by virtue of its greatest successes in the 20th Century. As the global population of our kind of musician has grown in the past two generations, the severely limiting nature of a career path that expects one to follow in Segovia’s footsteps or nothing has become a lot more obvious than it used to be. A lot of us would-be’s, I’ve often though, need to go from being classical guitarists who are musicians to being classical musicians who play the guitar. Without quite putting it like that, I was gratified to find that a leading mover and shaker in the business seems to think so too. And, what’s more, with the artists he works with and performers he supports, he’s doing a good bit to help make that happen! To the extent that repetition and dissemination have an effect in shaping the way people think about things, I thought it’d be worth my time to note the issues Alvaro and Bret talked about that resonated most with me.

Getting past exclusive soloism is a step in the evolutionary process for which the guitar is long overdue. And I don’t just mean we all need to add the Concierto de Aranjuez to our repertoire (though that would be a wonderful exercise in technical development, musicianship et al for most). If the guitar is indeed a versatile classical instrument that’s well-suited to a number of settings and configurations, and music from a number of periods, well – more of us need to play more of it, just like today’s ‘innovators’. Bret Williams does that, actually – he’s got an ensemble, whose membership and very composition just changed. Power to him; I hope his group gets that first record out soon.

There’s nothing wrong with the classical guitar repertoire, as Alvaro put it. The ‘old war-horses’ that most of us grow up longing to conquer will always have the power to move people. Recuerdos de la Alhambra will sound precisely as ethereal tomorrow as it did yesterday. Also, Sevilla or La Catedral will always prove a fair yardstick of one’s attainment of virtuosic ability. We don’t all need to write original music to be marketable – no other soloists do, after all. What would help, though, is not limiting the solo repertoire to what made sense, once upon a time, within a heavily Spanish- and Latin-influenced musical aesthetic. Fact – you don’t need to learn Asturias before you take on some Beethoven, and you’d still be just as much of a classical guitarist if you never played anything by Albeniz (and as we all know, he wrote for the piano, anyway). Some guitarists – John Williams being the highest-flying example that comes to mind – have looked to other places for dressed up, entirely concert-viable music. They didn’t do anything new by doing that, folks. They just opened up to more of the corpus of music that’s out there, everywhere. Perchance we could have some more of that Schubert fella?

Showmanship is another aspect of performance Alvaro and Bret talked about that I’ll confess I think about quite a bit, but am also a little defensive about, because I can’t quite come up with how a solo guitarist can be visually engaging for an audience. Recent research has shown the visual component to be a major factor in the overall success of a performance from the listener’s perspective, and of course a number of us know this to be true from personal experience (being on stage, as well as in the audience). Let’s face it – we’re not the most graceful spectacle in the world, nor the most engaging, through no fault of our form. There’s just not very much to see, and yet most of us are presented as the well-lit, mostly stationary, only thing on an empty stage when we play. I grant that the formality of classical music presentation demands this to an extent, and of course one mustn’t underestimate a cultured audience’s ability to feast to satiation even on such spartan fare. But for most people who like our music when they stumble upon it, but don’t seek us out (which is most people who listen to other classical music), performance requires more presentation.

So what do you do, unless you can actually play Chopin and Takemitsu one handed whilst standing on your head? In my humble o., you take a step back, and reassess what it is you’re selling. “Classical music, Yogi, you twit!” – one might well say. Yes, true. But what is classical music? It is something cooked to perfection, plated, and placed on a shelf for you to consume amidst your peers, much like a buffet at a ‘gourmet’ pizza joint? On CDs it is, maybe. In concert, it should not, and cannot sustainably be. I say classical music performance is about supplying a listener with an evocative experience, in which sound is the primary operant stimulus, but not the only one. It takes more than just good playing to move an audience. Setting and context count for more than most of us recognize. I actually want to take a leaf from the playbook of another industry that deals with fantastic things that take a long time to prepare, some time to present, and once consumed, are gone. I’m talking about food, of course. For example, there’s a new place in Shanghai called Ultraviolet, where the finest fare is presented in a manner that is appropriate to the qualities of the food, the quick n’ dirty expectations of our overly convenient and godless times notwithstanding.

I wouldn’t normally do this, but I think seeing the clip will get you up to speed on what I’m on about a lot better than my telling you about it, so here:

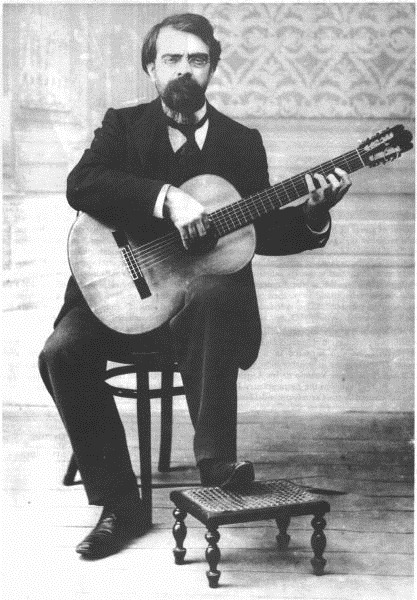

Now, I don’t know about gilded walls, antique furniture, flowers, and a glass of something nice with each ticket, but couldn’t we purveyors of spells for the heart and the soul do just a little more than diddly to take our listeners out of what amounts to cattle class, and put them in a setting where they’re better disposed to consume what we all agree is sublime? It’s a point that people involved with music make over and over again these days – more people would like classical music a whole lot more, if it were introduced to them properly. (Since I seem to be in a link-sharing mood today, I’ll also suggest you check out Benjamin Zander’s talk on the subject – search for it on youtube) With that said, wouldn’t it make sense for the industry (read: us) to take a few more of the steps of the interactive/consumptive process out of the consumers’ hands and, knowing a little about flash, bang, and romance, make a bit of an effort to set conditions that are favorable for more grace in their lives and more turkey on our tables? Could it be that the mass-production of concertized music has had its time in the sun, and must now be set aside as a sales model in favor of richer musical experiences for smaller groups of people, allowing more musicians to do more work better? As a side consideration, would doing so, in any way, effect a return to the performance philosophies of the likes of Tarrega and Segovia, for entirely modern, entirely hard-nosed, and yet artistically speaking, entirely valid reasons? Art is, of course, what we do – but it would be nice to get better at entertainment, and all the aspects of showmanship that the word entails – for that’s the only way enough of us will ever get to share our music with everyone else.